Joan Massagué And The Origin Of Cancer Metastases

Joan Massagué can be remembered as the man who discovered the origins of cancer metastases. A phenomenal scientific breakthrough that ultimately explains the way atypical cancer cells settle in other organs.

The researcher leads a research group at the Sloan Kettering Institute in New York City. There, they have been researching issues related to neoplasms for a long time, and therefore this discovery is part of a long journey.

Basically, the paradigm changed after we could explain that tumor cells replicate the way the body heals wounds to generate metastases. This article will explain how medicine had a different concept on this topic.

This progress is important because nine out of ten cancer patients die as a result of metastasis. That is why the publication of this research in the Nature Cancer Journal is a confirmation that there is hope of reducing this mortality.

As you will see below, the central axis of discovery is the tumor’s ability to produce the L1CAM molecule. It is the same substance that damaged tissue in the body makes to heal wounds. Hence the surprise.

What are cancer metastases?

Let’s first look at what metastasis is, to understand Joan Massagué’s discovery.

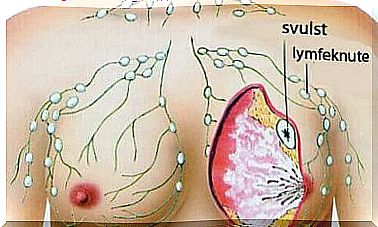

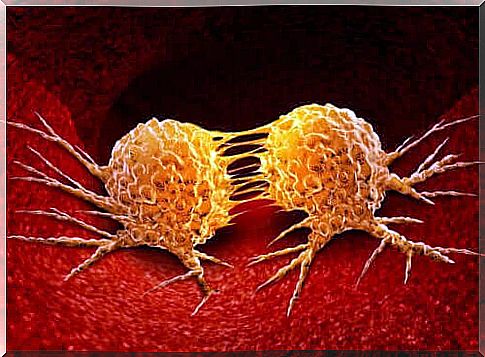

Cancer metastases are the occurrence of a primary tumor in another organ or tissue than the one that first gave rise to it. The cells migrate from the original site of cancer to settle elsewhere.

This seems logical and expected in the development of cancer, although research on the subject agrees that it is not so easy for a neoplasm to cause metastasis.

A metastatic cell must be able to separate from the primary tumor, move through the body and find a place to settle properly. There is no metastasis if any of these steps fail.

Different cancers have specific sites where they tend to metastasize. Breast cancer, for example, usually spreads to the bones and lungs. Prostate cancer also causes secondary bone tumors.

Lung cancer and colon cancer are usually located in the liver. Either way, any tissue can become a recipient of a neoplasm.

Previous belief in cancer metastases

Joan Massagué’s discovery of the origin of metastases shatters previous beliefs in medicine. It is, in a way, a complete reversal of scientific knowledge.

Traditionally, we assumed that cancer had a genetic component in mutation that resulted in metastasis. Tumor cells would migrate due to their ability to mutate and thus connect to other tissues.

People have questioned this traditional knowledge since the 1980s, although it persisted as it accepted. A researcher named Harold Dvorak talked about metastases as damage processes that failed to heal properly. This is related to the concept of the discovery of Joan Massagué and his team.

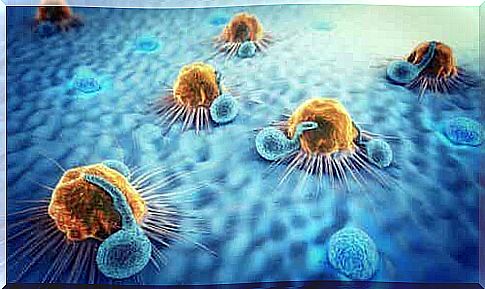

The origin of metastases is attributed to cell programming, but not mutation, in the new paradigm that this research means. This means that tumor cells do not mutate, but turn on or off genes they already have to migrate elsewhere.

Some cells homologate their behavior to the stem cells when they are reprogrammed. Thus, they generate affinity with another tissue.

What Joan Massagué discovered

Joan and his team studied metastases for years and already knew that only 1% of all neoplastic cells can migrate and metastasize before investigating the origin of this process.

This low incidence led them to ask why so few cells were able to do so, and research pointed in that direction. So they looked at the molecule L1CAM, which they knew finds expression in metastatic cells.

L1CAM does not occur in healthy body tissues, only in damaged epithelial cells. The human body uses it to repair wounds by bringing the cells together.

Metastases express L1CAM for adhesion, and simulate the normal wound healing process. Therefore, the research team defined the metastasis mechanism as the repair of a wound that is not a wound, in a place that does not have one.

Another study by the group led by Joan Massagué, also published in Nature , confirms that metastasis is due to reprogramming. Metastatic cells produce other molecules that are identical to those used by the body to fill wounds and form scars in addition to L1CAM.